I was reflecting, as one does, on why no one reads James Kelman, one of the great living fiction writers.

Obviously, this is not true. He won the Booker Prize for How late it was, how late; was shortlisted for the Booker for A Disaffection, which won the James Tait Black Memorial Prize; and there are a few more prizes thrown in. You will have no problem finding opinions and reviews of him on the interweb. He is known for writing about working class folks, often in Glaswegian or Lowland Scots dialect.

When he was awarded the Booker Prize, the columnist Simon Jenkins, writing in the Times of London, called Kelman “an illiterate savage” and the book, “the rambling thoughts of a blind Glaswegian drunk.”

My response: Sign me up.

(Disclaimer: I will read/watch read anything set in a grim urban setting, and featuring a lot of non-action and people smoking and drinking (e.g., the early films of Mike Leigh).)

Here in America, the only person I can recall who lit up when I mentioned Kelman was a guy named Frog, an amateur student of Irish, who I bumped into several years ago in a local taproom. Which perhaps made sense.

Perhaps if I was in the academic lit world, folks would at least know who he was. As an experiment, I took one of Kelman’s books to a recent gathering of writers, and asked the eight folks there if any of them had ever heard of Kelman. I got one maybe from a guy who teaches at aprestigious university but that was it.

This is not a survey, academic or otherwise, of Kelman’s work. I figured out many years ago that I was not cut out for that type of work. Rather, I hope to encourage others to check him out – he is a vastly engaging and entertaining writer.

Pictured at top is a pile of my James Kelman collection – minus duplicates and also my copy of Not Not While the Giro, his first short story collection, which I loaned to someone and never got back.

I would recommend starting with his short fiction, as it will introduce you quickly to his style, which usually features working class folks in Glasgow or elsewhere in the UK. Very often it is a monologue recounting a few hour’s events, which may be very mundane, voiced with heavy Scots diction and word choice.

Often the action is practically non-action. Here he describes drinking a beer:

This then might proceed to an objective, perhaps a bit distressed, analysis of a mundane situation; for example, the problem of a dwindling supply of cigarettes:

And from there, there can be a descent into more painful self-examination:

If this feels like Beckett, you’re on the right path. His characters are more rooted in the mundane than Beckett, but exhibit much of the same wry rationality and self-awareness of their pitiful condition.

For Kelman’s short fiction, really any of the collections will do as a starter, but my favorites are The Burn and Not Not While the Giro.

His novels run the gamut from . . . I’m not sure how to describe the range. The only ones I would provide any caution about are Translated Accounts and You Have to be Careful in the Land of the Free. I could not figure out what was going on in either of these.

How late it was, how late is a long monologue by a man who has lost his sight:

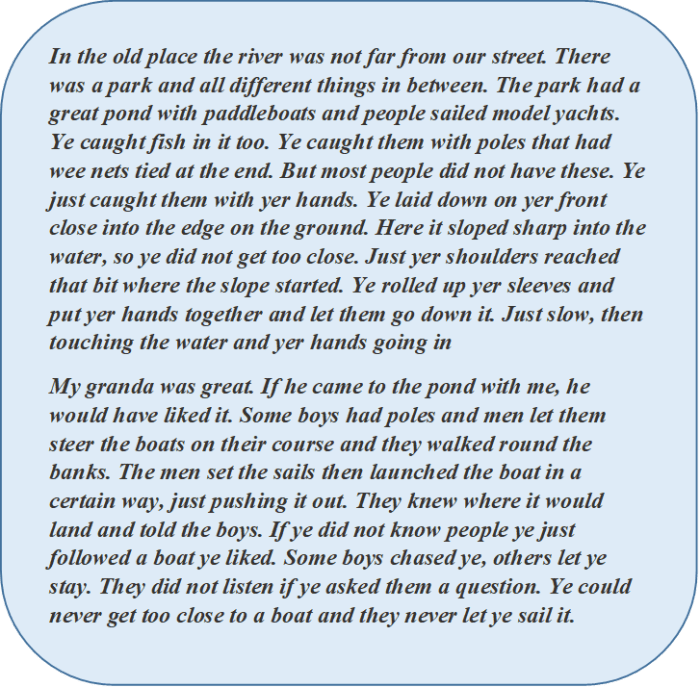

If that’s not your bag, then consider the two early character studies: A Disaffection, about an embittered, isolated school teacher; and A Chancer, about a gambler. His later works perhaps break out of the “sad guy” milieu. I recommend to anyone (not just fans of smoke and beer) Kieron Smith, Boy – a first-person narration by a ten-year old boy:

Mo Said She Was Quirky is a first-person narration by a white Glaswegian woman living in south London with an Anglo-Pakistani Muslim boyfriend.

Dirt Road, his latest novel, is a story told from the point of view of Murdo, a teenage boy, who has recently lost both his mother and sister, and has gone with his father, Tom, on a sort of bereavement trip to visit relatives in Alabama, where Murdo, an accordion player, meets a group of Zydeco musicians who embrace him and invite him to play with them at a festival in Lafayette, Louisiana, which leads to an impulsive run-away road trip.

In reading Kelman, I like the abruptness of endings; the absence of a mission; the obsession over small matters; the unlikely settings; the lack of smart observations by a narrator; the honesty of self-examination; and the discovery of drama in everyday life.

If your tastes run to the perfectly-crafted, overcoming-a-conflict, workshop-stamp-of-approval brand of fiction, then maybe Kelman is not for you. But to me his writing has a ring of reality and truth.

Note: All quotations in the boxes are from various works by James Kelman.

Thanks for the interesting and enticing account of James Kelman’s fiction. I have not read him but will choose one of the titles you helpfully describe. The array of quotes give us a good feel for Kelman. I appreciate your saying what you specifically like about him. I have a local friend with an academic past (retired lit prof) who taught Swift and Fielding for years but had some of us oldsters read Raymond Carver and George Saunders for a class. I will share your piece with him for a possible response.

LikeLike

You will find Kelman very different from Carver and Saunders, no negative on them.

LikeLike

Yes, I can see from the array of quotes you provided what Kelman sounds like. I mentioned that we’d read those other 2 because a) Saunders is transgressive and challenging in his own way (I actually did not like him much) and b) Carver writes in voices of characters of a lower social order. Some of his stories were funny for me although other people in our class thought, “Why are we reading this?” It sounds like a lot of readers don’t get Kelman either. Anyway I appreciated your article.

LikeLike