What can be said that has not already been said about James Whale’s masterpiece, Bride of Frankenstein (Universal, 1935)? Anyone likely to want to see it surely already has. So I will go light on the summary here, and focus more on the fascinating people involved in the production. Hopefully, this will provide the reader with a handful of tidbits to drop into conversation to impress friends with what a horror movie bore you are.

At the end of Frankenstein (Universal, 1931), the Monster had been assumed dead in the fire at the windmill. (In the original ending, Henry also died when thrown from the windmill by the Monster. However, Universal decided they wanted a more upbeat ending and added a coda where Henry is being nursed back to health).

Surprise! The Monster is discovered alive, kills a couple of incidental villagers, visits a blind hermit, and more mayhem ensues.

Henry is visited by his old mentor, Dr. Pretorius, played in gloriously camp style by Ernest Thesiger. Henry is trying to stay out of the Monster game, but Pretorius, who has created a few homunculi (small human type things) is itching to enlist Henry to create a spouse for the Monster. Henry says no but Pretorius, by now with Monster in tow on the promise of setting him up with a date, has the Monster kidnap Elizabeth (Henry’s wife), and Pretorius uses her as a hostage to compel Henry to comply.

Once Henry gets the bit in his teeth, he is gung ho. Female monster is created, the promised date is a disaster, Monster doesn’t take it well. Destruction follows, with appropriate poetic justice.

It is best to have seen Frankenstein before viewing the Bride.

Frankenstein is an amazing film, and its shocking (in 1931) horror and gloom set the stage for the more polished, audacious and camp Bride. The two leads appear in both films (Boris Karloff as The Monster and Colin Clive as Henry Frankenstein). Elizabeth (Henry’s fiancée/wife) is played in the first film by Mae Clarke, perhaps most famous as the recipient of the grapefruit-in-the-face from James Cagney in The Public Enemy, released the same year. Clarke appeared in six films released in 1931, including Waterloo Bridge, also directed by James Whale. Valerie Hobson (more on her below) plays Elizabeth in the Bride.

For both films, we have producer Junior Laemmle (left), son of Universal’s founder, Carl Laemmle to thank. He championed these and other horror products (notably Dracula, The Mummy and The Invisible Man) against the opposition of his father and senior staff at Universal. Frankenstein was a huge success.

The story of James Whale’s life from his “austere childhood in the Black Country” through his journeyman days as actor, stage manager, set designer and director in London, to his enormous, though short-lived success in Hollywood that included his 1936 version of Showboat, and his eventual professional decline and suicide in 1957, can be learned from James Curtis’s excellent biography, James Whale: A New World of Gods and Monsters, a must read for Whale fans.

That’s James Whale at the top of the post with Boris Karloff (in costume). Here’s another pic of the dapper Whale:

The dramatic imagining of Whale’s later years depicted in the film Gods and Monsters (1998), with Ian McKellan playing Whale and Brendan Fraser playing an innocent hunk of a gardener who becomes the object of Whale’s affection, is a touching tribute to a great artist.

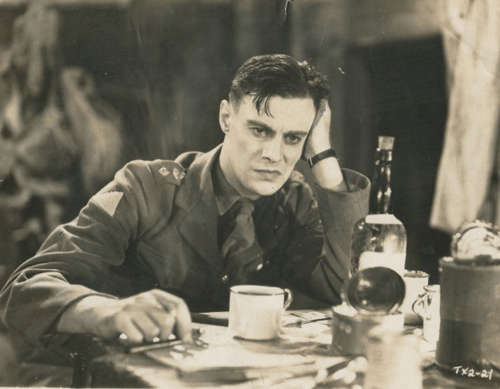

Whale’s theatrical breakthrough as a director was N.C. Sheriff’s Journey’s End, set in the trenches of World War 1. With Whale directing, the play opened at a small London theater in 1928, moved to the West End in 1929 and New York in 1930, and became Whale’s entrée to Hollywood. The film version, also directed by Whale, followed in 1930. Colin Clive played the lead, Captain Stanhope, in the West End and New York productions, and in the film. His performance as the tensely wound, battle-shattered Stanhope made him Whale’s choice for the tortured, obsessed Henry Frankenstein.

Here is Clive in the film version of Journey’s End:

In 1931, having made the forgettable Hells’ Angels and the memorable Waterloo Bridge, Whale made Frankenstein. Over the next four years, he directed six more movies (including The Old Dark House and The Invisible Man) before coming to the Bride.

Whale’s directorial skills and imagination in the creation of the film reflect the breadth of his theater experience, particularly in set design. The Monster in this film becomes more humanized, learning to speak a few words: good, bad, friend. Whale injected a good deal of humor into the film, largely through the “addition of two new characters: Minnie, a household maid played to shrill excess by Una O’Connor; and Dr. Septimus Pretorius, Henry’s philosophy professor, an arrogant old coot performed with arch effeminacy by Ernest Thesiger”, as Curtis puts it in the Whale biography.

Here are Thesiger and Una in the Bride:

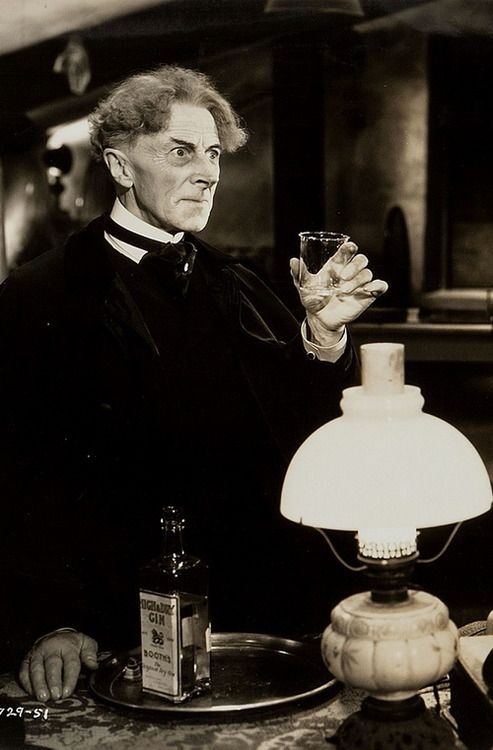

Thesiger and Whale were both openly gay, but Thesiger was more flamboyant. He called himself “the stitchin’ bitch” and displayed his artwork and needlework in his hotel room—complete with price tags. Thesiger was a featured performer in The Old Dark House, wherein he repeatedly utters the memorable line, “Have a potato”, as shown in this compilation of moments from the film.

Colin Clive, indeed a descendant of Clive of India, was a troubled alcoholic, who bore constant watching during the shoot to make sure he did not disappear into the bottle. His personal instability was perhaps linked to his ability to work himself to moments of hysteria on stage/screen, a trait that had made him Whale’s steadfast choice through the multiple productions of Journey’s End and his two Frankenstein films. Here he seems to be at one of those points in Frankenstein:

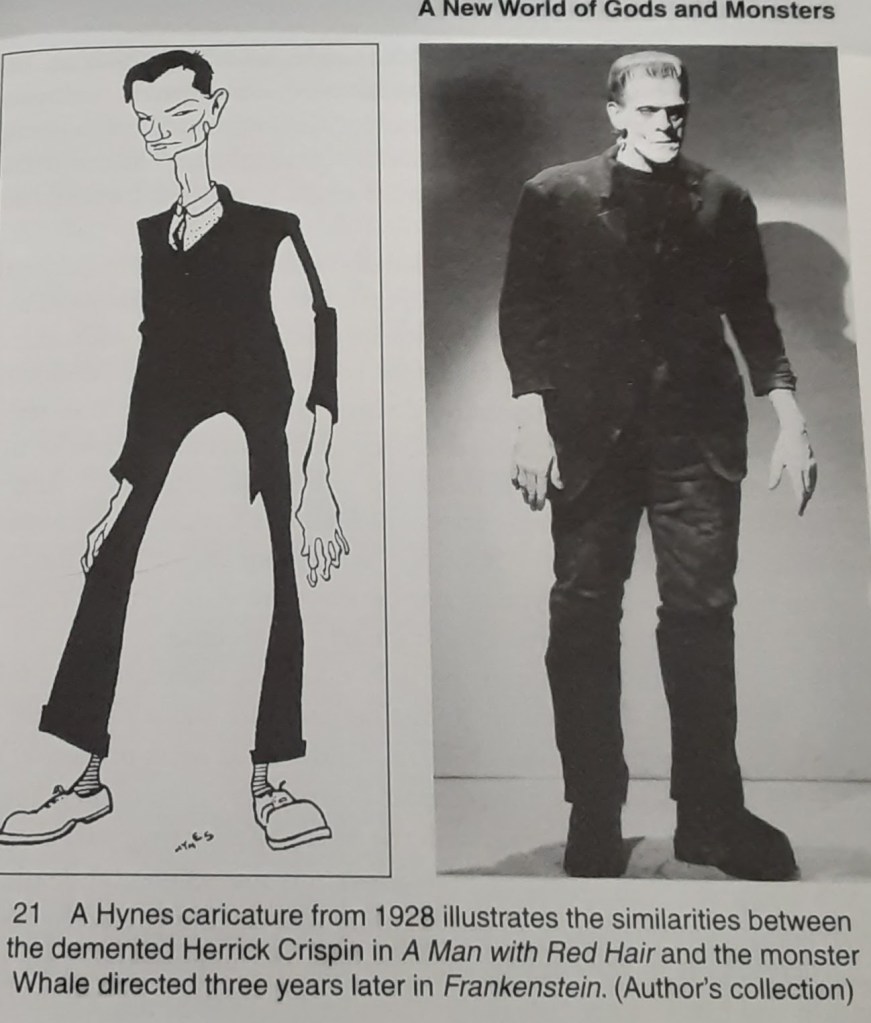

Which brings us to the Bride. For this role, Whale reached out to Elsa Lanchester, the wife of Charles Laughton. Both were colleagues from Whale’s early London theater days. Whale had recently directed Laughton in The Old Dark House, and the two had appeared together in a London production of A Man with Red Hair in 1928, with Whale playing Herrick Crispin, the loutish son of a macabre and sadistic father, played by Laughton. Herrick Crispin was perhaps an inspiration for the look of the Monster, as suggested by the caricature below (copied from Curtis’s Gods and Monsters).

Whale’s concept for the Bride’s look was brought to life beautifully through the artistry of Jack Pierce. Again from Curtis:

“[Pierce] approached the rendering of the Bride with a relish usually reserved for one of Karloff’s faces, decorating the actress with sexy stitching and wrapping her in yards of surgical gauze. A pink rubberized gown was draped over her, and a bird’s nest of a wig, built out on a wire cage with lightning-like streaks of gray, was fixed to the top of her head.”

Lanchester has said that her chilling depiction of the Bride, with her hissing and sudden birdlike movements of her head, was based on her observation of mating swans in Hyde Park. Here is the unhappy couple:

Valerie Hobson (Elizabeth in the Bride) went on to appear in Werewolf of London (1935), David Lean’s Great Expectations (1946) and Kind Hearts and Coronets (1949), the wonderful comedy starring Alec Guinness in multiple roles. In 1954, she married the MP John Profumo and stepped away from her film work shortly thereafter. Hobson stood by his side through the disgrace of the Profumo Affair and the quiet years of charity work that followed.

Here she is on the point of abduction by the Monster:

Then there is Boris Karloff. His work and voice are so well known that I will not belabor them. Here is a snap of Boris in one of my favorite roles, John Gray, a cab driver who moonlights as a grave robber, in Val Lewton’s The Body Snatcher (1945):

Serious Bride fans can refer to Curtis’ book, or scour the internet, for the contributions of Franz Waxman (musical score), John P. Fulton (matte work to bring Pretorius’s tiny homunculi into the film seamlessly) and Kenneth Strickfaden, who created the laboratory equipment, some of which was recycled from Frankenstein.

Finally, you cannot truly appreciate Young Frankenstein if you have not seen Whale’s Frankenstein films, and, more importantly, Rowland V. Lee’s Son of Frankenstein (a film deserving of its own blogpost). So, if you are among that group of Philistines, you have some work to do!

[…] The final installment in this much-delayed series on Halloween horror will focus on the great James Whale’s Bride of Frankenstein. […]

LikeLike