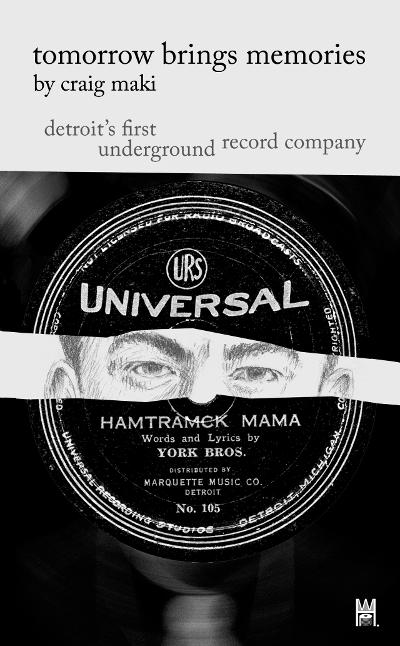

Maybe a year after I was gifted Mind over Matter: The Story of Fortune Records (see my review here), I received another Detroit-focused recording history book, this one from Wax Hound Press, tomorrow brings memories – detroit’s first underground record company, by Craig Maki, a pocket-sized, 100-pager on what may be Detroit’s first record company, Universal Recording Studios.

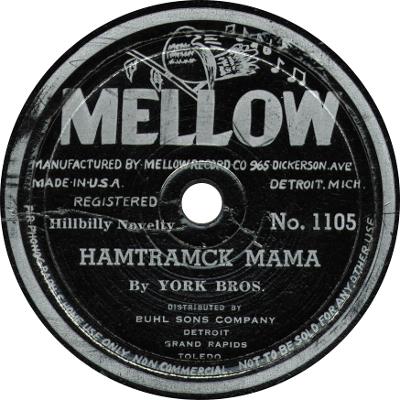

The books cross paths as The York Brothers, a country duo from Kentucky who made their way up U. S. Route 23 (the “hillbilly highway”) to Detroit in the late 1930’s, recorded their most infamous hit, “Hamtramck Mama”, in 1939 for Universal Recording Studios and the song was released under various Universal-related labels. Ten years later, Fortune Records released the same recording, which became a hit again and in fact was available through the 1960s. “Hamtramk Mama” was a bawdy country song, and Fortune mined that vein significantly over the ensuing years.

Maki is quoted in the Fortune tome and there is a blurb on the back of tomorrow brings memories from Michael Hurtt, co-author of the Fortune book. In my correspondence with Maki, he comments that Mind over Matter “deserves 10 out of 5 stars”. I concur.

The core of tomorrow is about Universal Recording Studios, which started as an audio transcription service in 1939 (creating small volume custom records and masters that could be pressed into multiple copies elsewhere), and evolved into a record label, or labels more properly: first Universal, then Hot Wax and Mellow.

This was all the work of Louie Shoun and Ed Kiely, a “shell-shocked WWI veteran and an ex-con” respectively, who came together to create these labels that flourished with issues of hillbilly novelty songs, as the records actually said; typically country songs with risque lyrics.

Maki hangs a number of riffs and threads off this through-narrative, including the story of how the recording industry evolved, how jukeboxes played into record sales and his own personal search to find the identity of the Shoun Brothers, who were credited with a song issued by Fortune through its Renown label, “Handy Man”, but who appear nowhere in the admittedly murky history and discographies of hillbilly music.

It is a personal book. Maki relates how he got his start into this deep history:

“Little did I know in 1998, when Detroit record dealer Cap Wortman lended me a plain cardboard box containing Universal, Hot Wax, and Mellow 78 rpm records from his personal collection, that a quarter-century later I’d write this book.”

Fans of Detroit country music (all two of us, as Maki wryly comments about another fascination) may be familiar with Maki from his DJ work at public stations in Southeast Michigan, and for the more reference-guide type book he coauthored with Keith Cady, Detroit Country Music: Mountaineers, Cowboys and Rockabillies, which I also recommend.

tomorrow is a book both anecdotal and dense. I’ve read the book through at least 3 times to get the various threads straight in my mind. There are over 100 footnotes in this short volume, and they are not of the Wikipedia-referencing sort. Among the sources cited are many newspaper articles from the 1930s/40s, records of Leavenworth prison, proceedings of the Un-American Activities Commission and personal interviews with many musicians.

Button Companies, Jukeboxes and Hillbilly Novelty Records

Maki’s recounting of early record production is fascinating, with records being manufactured at such places as the Bridgeport Die and Machine Company in Connecticut at the behest of the Wisconsin Chair Company, the Scranton Button Company, and J. L Hudson department store. The rise of jukeboxes in the depression came to dominate the listening habits of the public, with 60% of records being bought by juke box operators by 1937.

Louie Shoun was a veteran from Virginia with a club foot who participated in the Mexican Expedition against Pancho Villa under Pershing and in 1917 accompanied the American Expeditionary Force to France, allegedly as a personal aide to Pershing. Shoun had stints in vaudeville orchestras playing cornet and ended up in Detroit, where he learned to repair radios and phonographs and founded Universal Recording Studios, an audio transcription service, in 1939.

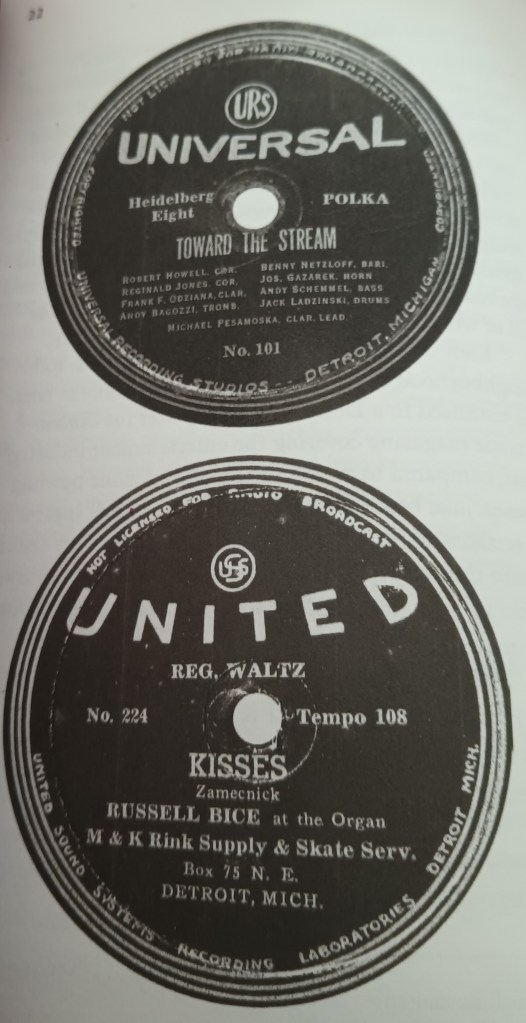

Universal became the first Detroit studio to be linked to a record company, beginning with a relationship with Marquette Music, which had itself evolved from creating coin-operated player pianos to games and slot machines and then juke boxes, and then in 1939 contracted with Universal to record the York Brothers’ “Hamtramck Mama”.

The record had the Universal logo, but said distributed by Marquette Music Co. For reasons not entirely clear, the Marquette name quickly disappeared (legal issues with the bawdy records?) and Universal went full bore into the record business. More “party” records ensued (e.g., “Detroit Hulu Girl”, “Highland Park Girl”).

Maki includes an extensive discography of Universal Recordings on its various labels, which included many salacious songs with a country edge. There is a lot here about the York Brothers, who cut many records for Universal before moving on to Decca in 1940-41.

One mystery that Maki tries to unpack is the relationship between Universal and the famed United Sound Studios, which was founded in the mid-1930s by Jimmy Siracuse as an audio transcription service and went on to record many famous artists over the ensuing decades (a partial list can be found here: United Sound Artists). Siracuse built his own cutting lathe and was rumored to have helped other recording studios in their early days. The United and Universal labels were very similar (see below). Maki speculates that Siracuse helped Shoun out in getting started with recording technology.

The Mysterious Shoun Brothers

The provenance of the recording of “Handy Man” by the Shoun Brothers, released in 1951 on Renown, an imprint of Fortune, is a mystery that only a true record hound could appreciate. This obscure 78 sounded to Maki like music of the 1930s. (Note: Discogs has one entry for the Shoun Brothers, a 45 release of the same recording from the late 1950s, priced at $400.)

Unable to find any information about or other releases by the Shoun Brothers, Maki kept asking around and searching the internet for twenty years. He finally came across a video of a group performing the song with the same instruments and arrangement as the Shoun Brothers recording. A comment to the video posting credited the origin of the song to the Shelton Brothers of Texas, who it turns out recorded the song on the flip side of a Decca recording in 1941. This was the same recording as the Shoun Brothers version on Renown.

The mystery of how The Shoun Brothers name came to be on the Shelton Brothers recording on the Renown subsidiary of Fortune will never be known, and I will let the reader discover the details of Maki’s speculation in his book. But let’s just say that it is a bit suspicious that Jack Brown, the owner of Fortune, acquired a number of master recordings from Universal in the late 1940s and that Louie Shoun ends up as the namesake of a seemingly non-existent country music duo.

Esoterica

Other tidbits include a Universal record authored by a retired major league umpire, George Moriarty, and recorded by The Four Dukes, “You’re Gonna Win That Ball Game Uncle Sam” in 1942; the US government’s restrictions on use of shellac in WWII (bringing to mind Richard Thompson’s line, “You just can’t get the shellac since the war”, in his song “Don’t Step on My Jimmy Shands”) that led to record companies pressing new records over old and a campaign by Kate Smith to collect old records and sell them to record companies and use the proceeds to send music and record players to boys overseas; and the story of Johnny Lavender, not a member of the New York Dolls but a bass player with an arched spine due to a childhood case of the rickets, who lent a comedic touch to performances with the York Brothers in a rube fashion not atypical of hillbilly bassists of the era.

For the record collecting enthusiast, there is ample discussion of the color of paper and inks on the various record labels, stamps and letters scratched into the runout section of 78s and gaps in recording catalog number sequences.

Zora Record Company

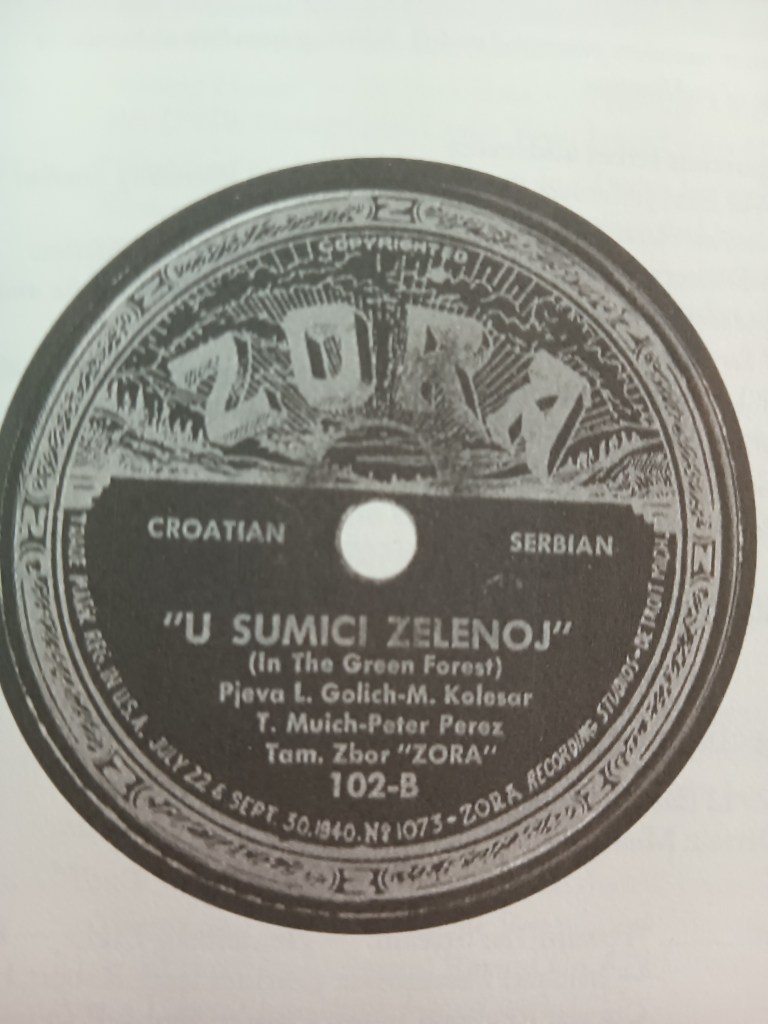

Maki closes the book with a charming postscript about a Croatian immigrant, John Dobranich, who performed traditional tamburitza music in Illinois, established the Zora Tamburitza Choir in Chicago and recorded a series of records for Victor in 1929.

The choir travelled throughout the upper midwest performing for Slavic communities and eventually settled in Wisconsin. Dobranich moved to Detroit in 1934, where he continued his musical activites while working at Budd Wheel Company, and formed the Zora record company, issuing about twenty 78s and one lp in the same era as the Universal stuff, including his tamburitza choir and other Croatian and Serbian acts. Zora’s output seems to have ended in the late 1940s, possibly due to censure from the post-war Unamerican Activities Commission, as Dobranich’s name appears in the proceedings as associated with the American Slav Congress.

In an instance of personal kismet, Dobranich lived his final years in Newaygo, Michigan, the rural county where I spend my summers and am writing this post.

This is a gem of a book, even if you are not a hillbilly music fan.

Postscript

A great interview with Craig Maki about this book appears on The Book Beat site. The link is below and goes deeper than my own post, I must admit!

Maki also created a playlist to accompany the book, which is presented here for your listening pleasure. And here is a link to his website Carcitycountry.com.

NOTE: Any errors here in my summaries of material from Maki’s book are solely my responsibility. Images are taken from Maki’s book.

IF YOU ENJOYED THIS CONTENT, PLEASE HIT THE SUBSCRIBE BUTTON BELOW TO BE NOTIFIED OF FUTURE POSTS!

[…] check out this post at Joel E. Turner’s “Fiction and Other Things” blog, in which he presents a […]

LikeLike