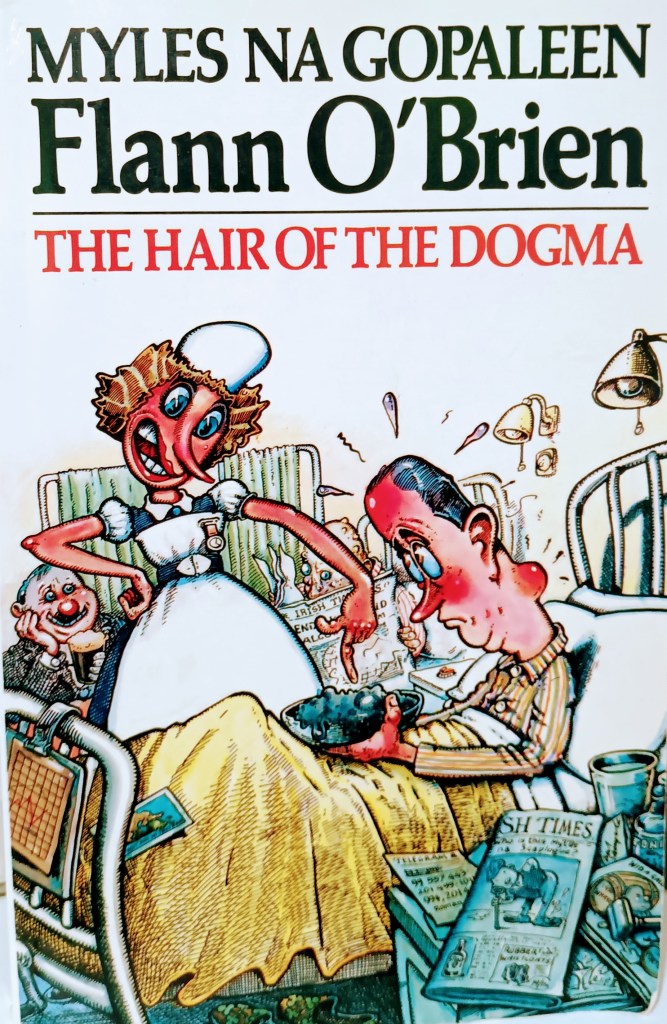

Myles na Gopaleen (Flann O’Brien) often spoke of Joyce in the Cruiskeen Lawn pieces he penned for the Irish Times from 1940 through the late 1950s. In one titled “J.J. and Us”, collected in The Hair of the Dogma, he bemoans the recent Penguin edition of Dubliners (ca 1956), which repeatedly refers to Finnegan’s Wake; the inclusion of the apostrophe he puts down to “negligence or ignorance”.

This mispunctuation really got under Myles’ skin, as evidenced by another column wherein he blasted an article in The Bell that consistently used the erroneous apostrophe: “That apostrophe (I happen to know) hastened Mr Joyce’s end. To be insensitive to what is integral is, I fear, not among the first qualifications for writing an article on Mr Joyce”. (The Best of Myles, Penguin Edition, p. 239).

Take that, you inserter of inappropriate apostrophes!

In “J.J. and Us”, Myles reserves stronger words for a misplaced comma in the story “Ivy Day in the Committee Room”, as rendered in the same benighted Penguin edition of Dubliners:

“But what words have we for this thing, on p. 128?:

Mr Lyons sat on the edge of the table, pushed his hat towards the nape of his neck and began to swing his legs.

‘Which is my bottle? he asked.

‘This, lad,” said Mr Henchy.”

“That comma after ‘this’ – have we a word for it? Yes: BLASPHEMY”

I checked a copy I have (Modern Library, 1969) and the comma was in its rightful place. This edition had corrected text by Robert Scholes in consultation with Richard Ellman, who would be the right boyos, as Myles might say. Whether Penguin originated this error, I will leave to folks who have studied all that.

O’Brien was a great admirer of Joyce and spun out fancies in his column that he and Joyce were in the same drinking circle (impossible as they were twenty years apart in age and Joyce was long gone from Dublin by the time O’Brien was getting plastered at the Scotch House), a circle that seems to have only existed within Joyce’s own texts.

When the Scotch House, O’Brien’s unofficial office to which he would repair (in Joyce’s Uncle Charles fashion) when his bureaucratic duties of the day were done (early, as I understand it), was to be sold, O’Brien (Myles, that is) unleashed a torrent of nostalgia in a Cruiskeen Lawn piece (“Black Friday”, also in The Hair of the Dogma) that is straight out of the world of “Counterparts”, a story in Dubliners, where he styles Joyce as the character O’Halloran. :

“There we were in a lump, all in strong body-coats, myself in the lead – Henry James, Bernard (‘Barney’) Kiernan, Hamar Greenwood, Meflfort Dalton, the Bird Flanagan, Jimmy Joyce, Harvey Duclos and MacCredy the cyclist, all heading into the Scotch House for hot tailers of malt, with a clove apiece thrun in to take the smell off our breaths. I remember cuffing a young fellow selling flags in connection with some ‘rag’ and being reminded by Joyce (who at the time called himself ‘O’Halloran’) that the da, Gogarty, was an important man.”

A bit later in the column, Myles quotes “Counterparts” verbatim and insists that he is Farrington, the clerk at the center of the story, who, in Joyce’s words is wed to a “a little sharp-faced woman who bullied her husband when he was sober and was bullied by him when he was drunk.”

Myles variously defended, satirized and lied about Joyce (claiming he had met him on various occasions, all apparently untrue). He even included him as a character in The Dalkey Archive though, to my taste anyway, there was little bite or humor in it, his talents by then flagging.

Anthony Cronin, in his excellent biography (No Laughing Matter: The Life and Times of Flann O’Brien), notes that “The figure of Joyce hung over his life like a sort of cloud from which the apocalyptic vision could come or had come. Like all revelations, it was resisted, distorted and, in part, rejected; but there was no disguising the fact that it had been vouchsafed”.